Rise of a Turbine Empire: The Tim D’Annunzio Story

Sunday, April 30, 2017

- Team FlyXP

- 4/30/17

- 0

- General, Skydiving

When you hear that Tim D’Annunzio is a founding member of the legendarily winning Golden Knights 8-way RW team–and the creator of the legendary Paraclete dropzone/tunnel complex–and a wildly successful entrepreneur–and a politician–you might wonder how he manages to pull it all off. Once you know a bit about him, it’s much less baffling, albeit just as impressive. After all, Tim D’Annunzio has been diving into challenges with both feet for a very long time.

When you hear that Tim D’Annunzio is a founding member of the legendarily winning Golden Knights 8-way RW team–and the creator of the legendary Paraclete dropzone/tunnel complex–and a wildly successful entrepreneur–and a politician–you might wonder how he manages to pull it all off. Once you know a bit about him, it’s much less baffling, albeit just as impressive. After all, Tim D’Annunzio has been diving into challenges with both feet for a very long time.

“I grew up in the city,” he explains, “And I was in a lot of trouble most of the time. Back then, the army had a loophole where you could just go before a magistrate and say ‘I swear I’m 17 years old’–which I did, and they let me right in. It was what I felt I had to do.” Tim joined the army when he was just 15 years old, in 1973, during the Vietnam War. He went to jump school right after he turned 16.

“When they found out how old I actually was, they offered to let me stay in,” he continues. “They would just pull me out of duty–get me doing something else–until I hit my 17th birthday. I declined.” He came back in 1977 when he was of legal age. After having completed training, he went to Fort Bragg.

“I tell people the army saved my life,” Tim explains. “In the Army, I had a complete turnaround from where I grew up and how I grew up. It suited me much better. The first month I got back into the service–May of ‘78–I was looking for something to do, because I didn’t want to get caught up in the barracks life, sitting around partying all the time.”

“I tell people the army saved my life,” Tim explains. “In the Army, I had a complete turnaround from where I grew up and how I grew up. It suited me much better. The first month I got back into the service–May of ‘78–I was looking for something to do, because I didn’t want to get caught up in the barracks life, sitting around partying all the time.”

The answer was, naturally, up.

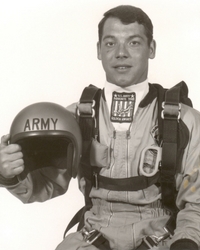

“I found a skydiving club. Fort Bragg actually had three of them. I joined the Green Berets Parachute Club. After I was jumping with those guys for two years, I went out to the tryouts and made it onto the Army team. I spent the first year on a demo team.” At the time, Relative Work–“RW”–had only been around as a discipline for a couple of years. The Army already had a 4-way team, but they were looking to expand into 8-way.

“They picked up four more of us who weren’t real hardcore competitors,” Tim remembers, “And we had to build this thing from the ground up. It was a long process, and we had to work hard on it every day. It was frustrating, sometimes, especially because the other 4-way team at the time–the guys we were thrown in with to make the 8-way team–were the reigning world champions. We were training with them, and we knew that was the level we were expected to get to. It didn’t happen all at once, and I wasted some time and energy pulling from the front.”

Tim competed “pretty consistently” for the next decade. At the same time, he did his full-time day job, also at the dropzone: as a full-fledged military freefall/HALO instructor with the U.S. Army Special Warfare Center and a master rigger. Back then, the former gig–military freefall instructor–was incomparably different to the same job as it’s performed now.

Tim competed “pretty consistently” for the next decade. At the same time, he did his full-time day job, also at the dropzone: as a full-fledged military freefall/HALO instructor with the U.S. Army Special Warfare Center and a master rigger. Back then, the former gig–military freefall instructor–was incomparably different to the same job as it’s performed now.

“Back then, there were no wind tunnels,” Tim explains, “And this was before AFF. The static line progression was the way you learned back then, and the way we trained people for freefall when I first got to the military was to put them on a table for three hours and show them what their body position should look like. Then each individual instructor would take two students up in the plane. That ratio is, of course, reversed today.”

“We would show them how to exit, and then the two of them would exit the airplane,” he continues. “You had to watch both of them.” It was a near-impossible job, of course. “For the first class I did, I had just come from training for the 8-way team, so I thought there was nothing these students could do that could surprise me. But when we all got out, one spun one way and one spun the other.” The two students were immediately dropped from the course, and Tim went back to it with a mouthful of humble pie.

After a few years on the circuit, Tim started to burn out on competition (though did enter the Nationals with a throw-together team of civilians, two years after ‘quitting,’ and took the gold in 1987). Tim left the Golden Knights in 1985 when he received an honorable discharge at the rank of staff sergeant. He went right over to the new job waiting for him: as a parachute rigger for space shuttles. For that gig, he moved to join Martin Marietta Aerospace at the Kennedy Space Center.

“It sounds like it would be a really exciting job,” Tim laughs, “But considering what I had come from and what I’d spent so much time doing, it actually turned out to be pretty boring and very slow-paced. You had to wait for several different quality control people to come and stamp off what you just did, no matter how simple. In some cases, that could take hours of just sitting there, doing nothing, waiting for the next stamp to happen. In the Army, we had a saying: ‘If you have to sit around and do nothing, don’t do it here.’ If we had nothing to do in the Army, we were told to go home. I don’t like to be idle.” He only stayed at the Space Center a year.

That work ethic has served Tim immensely well as an entrepreneur and a dropzone owner–the latter, as it turns out, of the very dropzone he’d spent endless hours on, training with the Golden Knights. That said, the road to dropzone ownership was by no means direct.

“I started jumping here in Raeford in 78,” Tim explains. “When I was on the team, this was where we showed up every day to train, just like every other guy in the military goes to his duty station. Raeford has always been my home dropzone.”

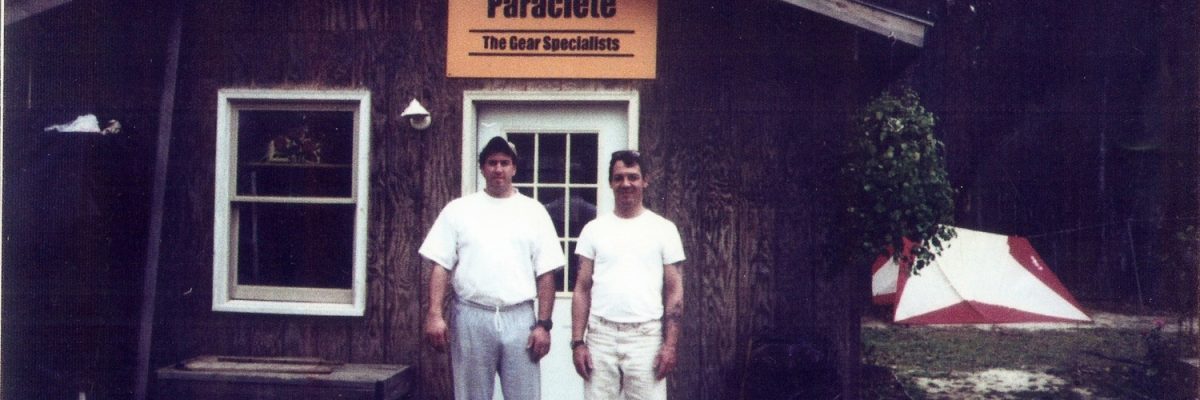

It was Raeford where Tim started his first entrepreneurial venture: a sewing business. “I built it up at varying stages of success and failure,” Tim grins. “The first business went under, but we recovered. I started making jumpsuits and things like that–things related to free-fall. Eventually, that morphed into us making body armor; military equipment; things like that.”

It was Raeford where Tim started his first entrepreneurial venture: a sewing business. “I built it up at varying stages of success and failure,” Tim grins. “The first business went under, but we recovered. I started making jumpsuits and things like that–things related to free-fall. Eventually, that morphed into us making body armor; military equipment; things like that.”

To be clear: we’re not talking about just any body armor. Tim’s brainwave was about combinatorial creativity: meshing parachute technology, which he intimately understood from his skydiving and rigging background, and combining it with body armor, which he’d been exposed to since he joined the Army at the age of 15. Tim’s body armor design was modular and had skydiving-inspired features that proved lifesaving: like a cutaway system integrated into the armored vest. The government “took that idea and ran with it.”

The company grew like wildfire. In its peak, it employed 350 people in a 144,000-square-foot manufacturing facility. The company was called Paraclete Armor and Equipment Incorporated. ‘Paraclete’ has, of course, become a very famous name indeed in the skydiving community, albeit in a totally different context.

Tim sold that first ‘Paraclete’ in 2006, for “more than [he] ever thought.” When he did, he already had plans for the windfall. He was going to build one of the nation’s first vertical “indoor skydiving” wind tunnels, and it was going to be epic.

“At that point, there were no civilian wind tunnels,” Tim recalls, “But there was a military indoor skydiving training facility up at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, in Ohio. We started taking students up there whenever a new class would come in. We would stay there for a week, and they would do wind tunnel training instead of ‘table time.’ The retention rates went through the roof. I knew it would be a great training tool for sport skydivers–and just something to do for fun, besides.”

When Tim sold Paraclete, the first thing he did was invest it into the wind tunnel idea.

“I made it more elaborate than it should have been,” he laughs. “We wanted to make it the best and biggest in the world.” Tim dove into designing it. Some of the groundbreaking innovations he introduced have become commonplace in the new tunnels popping up like springtime mushrooms around the world: the immediate prominence of the flight chamber upon entry; the expansiveness of the space; the classrooms; the comfort of the observation area. Since he’d built it with the express purpose of being big enough to train for his beloved 8-way RW discipline, the tunnel was officially the biggest in the world. Tim bought all the property around the facility–and drew a cream-of-the-crop staff of instructors and management from all the lofty corners of the skydiving industry that he’d come into contact with during his many years of instructing, competing and coaching.

“I made it more elaborate than it should have been,” he laughs. “We wanted to make it the best and biggest in the world.” Tim dove into designing it. Some of the groundbreaking innovations he introduced have become commonplace in the new tunnels popping up like springtime mushrooms around the world: the immediate prominence of the flight chamber upon entry; the expansiveness of the space; the classrooms; the comfort of the observation area. Since he’d built it with the express purpose of being big enough to train for his beloved 8-way RW discipline, the tunnel was officially the biggest in the world. Tim bought all the property around the facility–and drew a cream-of-the-crop staff of instructors and management from all the lofty corners of the skydiving industry that he’d come into contact with during his many years of instructing, competing and coaching.

The 4-way and 8-way teams started to flow in. After some time had passed, Tim’s team took over the management of the closeby Raeford dropzone. They signed a 20-year lease for the entire airport and all its operations, then started to stock it up with great aircraft. At publication, the Paraclete dropzone had nine shiny turbine aircraft snuggled in its hangars, and that number is only growing.

As Paraclete was gathering steam, Tim was, too–for public service. “I’ve run for the U.S. Congress and Senate,” Tim says. “I’ve run four times over eight years, and I think I’ve pretty much finished with that. I can’t win; my opponents always drag out the trouble I got into when I was a kid.” He laughs, good-naturedly. “Politics makes anything else I have ever done seem calm and civilized.” For a lifer skydiver, that’s saying a lot.

As Paraclete was gathering steam, Tim was, too–for public service. “I’ve run for the U.S. Congress and Senate,” Tim says. “I’ve run four times over eight years, and I think I’ve pretty much finished with that. I can’t win; my opponents always drag out the trouble I got into when I was a kid.” He laughs, good-naturedly. “Politics makes anything else I have ever done seem calm and civilized.” For a lifer skydiver, that’s saying a lot.

The political arena doesn’t know what it’s missing, but the skydiving industry is incredibly lucky to have Tim’s full attention. Since the day it opened its doors, Paraclete has enjoyed an unequaled position as the training destination for sport skydivers and military. In an industry that clamors for tandem and first-time-flyer business, Paraclete stands distinct in its commitment to athlete progression.

“We intentionally want to be a tunnel and dropzone by and for athletes,” he insists. “We’re in it because we’re competitors, too. We want to see the sport progress–and our fellow athletes progress. We want them to have the best training and the best facilities, and not treat them like nameless, faceless entities that get in the way of our birthday party business; like they’re somebody just coming in for a minute, to be pushed through as quickly as we can. We’re here for the sport. That’s why I started this place, and that will never change.”

“We intentionally want to be a tunnel and dropzone by and for athletes,” he insists. “We’re in it because we’re competitors, too. We want to see the sport progress–and our fellow athletes progress. We want them to have the best training and the best facilities, and not treat them like nameless, faceless entities that get in the way of our birthday party business; like they’re somebody just coming in for a minute, to be pushed through as quickly as we can. We’re here for the sport. That’s why I started this place, and that will never change.”

Tags: Tim D’Annunzio

Copyright © 2025, Skydive Paraclete XP, All Rights Reserved.

DropZone Web Design & Marketing by Beyond Marketing, LLC